As mentioned previously, I've been preparing some papers—both written and spoken.

The content of this post forms part of what became my university confirmation seminar paper. It will also be published in a forthcoming journal article. It is an introductory section, concerned with getting some of these ideas around

ostalgie to crack a bit under the weight of analysis, to push the "object to the point where that object destroys its own illusion," as Mr

Bctzoiwp puts it. I am talking here and in the paper more broadly about the relation of nostalgia to three films—

Sonnenallee,

Good Bye Lenin! and

The Lives of Others.

~

It's reported by Edward S Casey that there's a piece of graffiti in Paris that reads: 'Nostalgia is not what it used to be.' This says a lot and opens a few gaps for thinking about the topic. One of the questions rarely asked by cultural analysis of ostalgie is a simple one: what is nostalgia? Is it: a state of being, that is an ontological homesickness; is it a kind of pathology or recurring error; is it a form or phase of mourning; is it a transient disposition due to circumstances; is it a mere passing mood, encountered about 3pm each Sunday afternoon? The common, everyday response, of course, is pejorative. Nostalgia is a longing for the past which buffs away rough edges, a kind of soft-focus history. It's, at best, diversionary and pleasant, at worst, wrongheaded and dangerous.

To complicate this with some more precise terms and reflection, we can propose that: nostalgia is a feeling at the interface of individual and collective remembrance. It is often a personal mode of remembrance populated by items belonging to the 'collective'—that is, circulating goods and specific locations. It's often a compression of time and place, biography and history. As Casey writes, "this paradoxical interplay of the definite and the indefinite in space as well as in time…gives rise to nostalgia's baffling combination of the sweet and the bitter, the personal and the impersonal, distance and proximity, presence and absence, place and no-place, imagination and memory, memory and nonmemory." This is one of the chief reasons for its conceptual difficulty.

However, in discussing cultural forms—films or otherwise—we get access to one juncture of the individual-collective interaction, be it set up in distinction or compliance with the common understandings of particular plots of collective memory. Refining further, we could say: nostalgia represents a mode of orientation to the past, an act of remembrance calling on social cues and individual biography. To say this, though, is to open up another question elided by much discussion of ostalgie: where does nostalgia reside? Often, films and other cultural forms are invoked as 'ostalgic'—but is it possible that a reel of celluloid or a book alone can be nostalgic? I will not answer this question here, but it forms a kind of background thought throughout much of this essay. I will return to it in closing.

One matter which recurs in the broader literature on nostalgia is the feeling of a deepening in its presence over the past thirty years in the West. To provide only a quick catalogue of the reasons given for this: we are embedded an overarching 'postmodern' epoch; we have seen the rise of visual, screen culture; the decline of long-running personal and institutional attachments through the individuation of 'second modernity'; an amnesia in contemporary culture, despite ever greater digital archives. In many senses, then, according to these accounts, all three of the films analysed here are films of their time. For one, they fit within a broader movement of nostalgia films seen over the past three decades, a cultural mood about which Pam Cook's writings on British and Hollywood nostalgia films makes us aware. And all three are undeniably postmodern nostalgia films in Jameson's sense, rendering the past in a 'consumable set of images,' ticking all the boxes he offers: 'music, fashion, hairstyles and vehicles'. They carry within them an inventory not of 'facts or historical realities (although [such a film's] items are not invented and are in some sense 'authentic'), but rather a list of stereotypes, of ideas of facts

and historical realities.' In Jameson, of course, this links up to a broader denigration of postmodern nostalgia culture—denigrated for its purported lack of depth and its association with a crass commercial culture—a position which I do not wish to take up and which has already been widely critiqued. I would briefly note here, though, that both Sonnenallee and Good Bye Lenin! derive much of their comic value from dealing ironically and subversively with the very stereotypes they show on screen.

Thus if Jameson's description of the 'nostalgia film' on one level rings true but can be seen as problematised by at least two of the films discussed here, those films also underscore a problem with the negative cast nostalgia generally receives in the critical corpus. For one, these po-faced theories are inadequate in the face of comedic and ironic deployments of nostalgia. Yet perhaps the bigger problem with the dominant denigration is its paralysis on questions of the losses to which nostalgia may be a response—even as it's laughing. At its worst, such a negative characterisation of nostalgia does not admit of the pleasures nostalgia can offer—therein foreclosing a genuine understanding of the feeling, disregarding the phenomenology of the nostalgic. This confusion is understandable, as I have noted. Nostalgia is notoriously hard to pin down: 'nostalgia remains unsystematic and unsynthesizable,' Boym writes, 'it seduces rather than convinces.' Across the diversity of understandings and interpretations, across its manifold attachments to the present and politics, nostalgia culture is saddled with a paradox, as Radstone has outlined: "While [on the one hand] nostalgia is criticised for its commodification of the past—for its transforming of the past into a publicly traded commodity—it is also [on the other] conversely criticised for turning social change into private affect."

So if nostalgia is thus swatted every which way it turns, how can we turn it into a productive concept? A number of theorists—from Linda Hutcheon to Foucault to a handful of lesser known psychoanalysts—have offered relatively nuanced takes on the phenomenon. Psychoanalysis directs us to the essential basis of nostalgia: another version of the 'grass is always greener' modality, nostalgia functions as a necessary psychic buttress, a sunny counterpart to the ongoing disappointments in failing to achieve contentment. This is psychoanalysis in its anti-utopian mode. Beyond such a psychoanalytic account, Russian-born US-based academic Svetlana Boym has given us a useful schematic for post-communist nostalgia in the characterisation offered in her book The Future of Nostalgia. This dyadic scheme disarticulates divergent responses to the same impulse, to the seeking of comfort in the past—one of them unaware of its nostalgic gloss, one playfully aware of its daydreaming. Such a characterisation fits with the two dominant yet divergent critical accounts of nostalgia, but Boym valorises them in a way different from other writers: at one end, the consumerist and playful version of nostalgia, usually derided, is offered as a positive, or at least amiable and harmless, style of remembrance; at the other, a bracingly serious, politically valenced embrace of what we might sometimes call 'invented traditions,' is held to be dangerous. To explain this distinction further: Restorative nostalgia, for Boym, defies a linear conception of history in the quest to reconstruct a lost home, understanding itself as seeking truth and tradition. Dead serious, it reconstructs 'emblems and rituals of home and homeland in an attempt to conquer and spatialise time.' This is the type of nostalgia at the heart of much nationalism. Reflective nostalgia, on the other hand, circles the past in a wistful and ironic fashion. It dwells, ambivalently, on longing and belonging. It has no singular plot, ranging across dispersed places at once; ensconced in details, not symbols. Reflective nostalgia in this mode is 'not merely a pretext for midnight melancholias'—it is more creative and useful than the common caricature of nostalgia would allow.

While helpfully moving us away from commonplaces about nostalgia, this bifurcated scheme is limited in what it can proffer for the analysis of Ostalgie. Boym is upfront in admitting that these two forms are endpoints on a continuum of nostalgia types. She also offers some illuminating examples of cases she sees fitting these types of nostalgia. Nevertheless, such clear-cut binary categories ultimately offer an all-too-easy checklist, a kind of shortcut to analysis. If we follow her model, the meanings and significance of these nostalgias—what might be called their politics—go unnoticed. As Radstone reminds us, "debates concerning the politics of nostalgia require analyses of nostalgia culture that differentiate between its varieties, and that attend to the specificities of nostalgia culture's representations of the past, its strategies of address and its appeal." That is to say, an analysis that merely noticed ostalgic phenomenon and shifted them into one of Boym's two categories would be deeply flawed—one must draw apart this simplistic 'ostalgie' concept, to name its parts, to precisely call it by different names, to notice different species, different attenuations, different imperatives. The journalistic tendency to conflate ostalgie pays little attention to these qualitative differences. German reportage on this score does, of course, vary from the warmly dismissive to the tabloid panic styles, but in some ways this just alerts us to the need to avoid the temptation to come up with similarly neat categorisations in an academic context. This requires reflection on the very status of nostalgia. One of the questions we should ask of these films, for example, is a complex one: what makes a film about memory and not history? These two terms—memory and history—form a binary which has structured much recent academic analysis. This is literature which I do not wish to navigate here, but the distinction remains worth keeping in mind: why have these films been classified as nostalgic? Are the films—as texts—nostalgic? Or do they merely depict nostalgia? Are they not just more in a line of German historical dramas? If not, how are they different?

As I have already implied, ostalgie could be both of Boym's forms at the same time. It can be: postmodern capitalism's 'playful reappropriation of the everyday objects of East German culture,' be it the market in GDR pedestrian traffic lights or the Trabant car; or Ostalgie 'may be a reclamation of one's own biography, recalling happy times that are excluded from those discourses that reduce life in the GDR to the experience of oppression'; or, perhaps in a more fundamentally political way, it can represent 'an insistence upon a distinct set of East German values born out of the GDR past, such as a solidarity that challenges the supposed 'Ellbogenmentalität' [elbowing-out mentality—i.e. single minded pursuit of one's own interests] of Western capitalism.' These three types—and there are more—interleave in manifold ways. Radstone alerts us to this complicated tenor of any nostalgia—the manner in which affect, politics, biography and time blur in a text or set of texts that might all too easily be cast as nostalgic. The question must always be, nostalgic for what, for when, for whom—and, if it seems relevant, to what end. In analysing these films, then, we need to be awake, all at once, to the textual specificities of film—that is, its address, its appeal, its narrative choices—as well as to the historical and political specificities of production and reception.

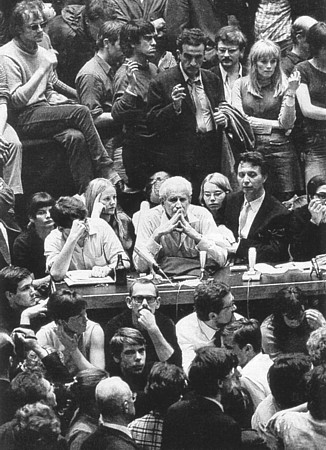

Image taken from German Propaganda Archive.

First in the US, now here: the fronts of the neocon culture war passing over the universities seem (surprise!) to be misguided.

First in the US, now here: the fronts of the neocon culture war passing over the universities seem (surprise!) to be misguided.