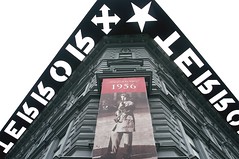

In her book on the remembrance of Hungary 1956, James looks at both 'official' and 'unofficial' collections or museums. This distinction divides her analysis. Both, she implies, contribute something different to the discursive construction of '56. One is the work of a street fighter from the time -- now accused of nationalism and connections with the far-right -- and the others the state-run Hungarian National Museum and the Military History Museum. There is also now the Terrorhaza (House of Terror), a state-run, embattled museum of Communist terror. It's worthy of its own post.

In her book on the remembrance of Hungary 1956, James looks at both 'official' and 'unofficial' collections or museums. This distinction divides her analysis. Both, she implies, contribute something different to the discursive construction of '56. One is the work of a street fighter from the time -- now accused of nationalism and connections with the far-right -- and the others the state-run Hungarian National Museum and the Military History Museum. There is also now the Terrorhaza (House of Terror), a state-run, embattled museum of Communist terror. It's worthy of its own post. The first official exhibition about the revolution in 1956 was held in June 1957, documenting the "counter-revolutionary events" of 1956 at Contemporary History Museum. Another exhibition was held here in 1989, lasting a month and titled "Objects, Documents, and Photographs, October 23-November 4, 1956." The main exhibit is now at the Military History Museum.

The first official exhibition about the revolution in 1956 was held in June 1957, documenting the "counter-revolutionary events" of 1956 at Contemporary History Museum. Another exhibition was held here in 1989, lasting a month and titled "Objects, Documents, and Photographs, October 23-November 4, 1956." The main exhibit is now at the Military History Museum.The unofficial exhibition is in the Hungarian countryside. The 1956 Museum is run by Gergely Pongrátz. He was a leader of insurgents and fled the country when the Soviets began attacking. He only returned in 1991 "after some thirty-five years of exile 'to tell the truth about 1956'." James:

A number of ideological questions are at issue in competing currents of popular thought about Hungary's 1956 revolution: What social group instigated the uprising? Who were its heroes? Who was to blame for its failure? What are its implications for Hungary's position in the international community today? And who can be trusted, both within and beyond the nation's borders?There's some nice references on museums here. Appadurai and Breckenridge express the role of the public museum well when they say, via James' paraphrase, "the museum presents static displays through which group identities are fixed and stablized as artefacts and are abstracted from their dynamic contexts." While Eilean Hooper-Greenhill (2000, 124) "writes that the interpretation of visual culture in museums can be approached from the point of view of the curator or the visitor." James' concern is with the curator.

Ordinarily this mode of institutionalising the past is directed by national governments. In Hungary, for instance, public museums are under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of National Cultural Heritage. But Raphael Samuel argues for the significance of the amateur museum as a site for the construction of collective memory.These amateur museums, as we see in the 1956 example, are still thoroughly ideological.

This seemingly capricious collection locates the revolution within a broader conservative ideology of traditional, Christian nationalism that comes from the heart. While the museum owner has carefully and methodically assembled a narrative of 1956 through the material culture available to him, he has done so on the basis of principles that are held at a deeply intuitive and emotional, rather than cognitive, level and derive from the authenticity of experience.

The conservative ideology that frames the production of culture in the 1956 Museum requires elaboration. Analyses of conservatism in post-communist Central and Eastern Europe tend to emphasise its most extreme, protofascist, anti-Semitic forms. (In Hungary this usually means focusing on ultraconservative writer and politician István Csurka.) Sabrina Ramet (1999, 18-19) writes that at the core of radical-right beliefs is 'an ideological and programmatic emphasis on 'restoring' supposedly traditional values of the Nation and imposing them on the entire Nation or community.This fits with the outline of "restorative nostalgia" theorised by Svetlana Boym. For Boym, this juxtaposes with "reflective nostalgia":

- Restorative: this stresses nostos (home), defying a linear conception of history in the quest to reconstruct a lost home. It is not self-consciously questing, however, but understands itself as seeking truth and tradition. It "protects the absolute truth." This is the type of nostalgia at the core of revivals in nationalism and religion. Its plot is that of a return to origins or conspiracy. It prefers pictoral and oral culture. Dead serious, it reconstructs "emblems and rituals of home and homeland in an attempt to conquer and spatialise time."

- Reflective: this is longing itself, algia. It "delays the homecoming," circling in a wistful, ironic and desperate fashion. Consequently, it dwells, ambivalently, on longing and belonging. It is embedded -- without struggle -- in the "contradictions of modernity". It questions -- even doubts -- "truth". It has no singular plot, ranging across dispersed places at once; ensconced in details, not symbols; it imagines different time zones. At its best, it can challenge, ethically and creatively, modernity, progress, truth -- and their assumptions. In this mode it is "not merely a pretext for midnight melancholias"; it is more creative and useful than the common caricature of nostalgia would allow.

James' discussions with Pongrátz, curator of this 1956 "collected memory," are interesting in this context.

Many years later, he continued, Boris Yeltsin visited the United States and stated on television that the downfall of communism started in 1956 in Hungary. 'So these kids,' he added, 'they weren't making only Hungarian history; they were making world history. Thanks to these kids, the whole communist system collapsed' (Pongrátz 2000).An analysis of the arrangement of collections follows. "Walter Benjamin (1968, 67) once observed that 'the phenomenon of collecting loses its meaning as it loses its personal owner. Even though public collections may be less objectionable socially and more useful academically than private collections, the objects get their due only in the latter.' The emotional power of the collection displayed in the Military History Museum is indeed blunted by its abstraction from the lived social world."Both of these exhibits...locate the revolution within a narrative of oppression, triumph, betrayal, and ultimate victory. This theme is subtly but forcefully written into the carefully scripted exhibit of the Military History Museum. The eclectic nature of the 1956 Museum's holdings, together with their more whimsical arrangement, invites a more imaginative reading that centres around the romantic image of the courageous and selfless young street fighters.

Again, on the public/private collection difference, James finishes her chapter discussing the homely presentation of objects in the unofficial museum.

Here the vase of chrysanthemums departs entirely from professional display practices. Viewers are not only reminded of a shrine, they are forced to realise that someone has made this shrine. And therein lies the unintended emotional power of this display and of the 1956 Museum as an institution: it speaks to the human drive to honour and preserve the past regardless of the limitations of the composer.For me, the interest lies in the way these museums tell the same history. Or, better put, the way they narrate the same event. Their imperatives are not so different, in the end. Wishing to unite the nation in the restorative way Boym outlines. This is not so surprising in the case of the national institution, but its romantic evocation in the private collection is not so inevitable. James comes away from the private collection at once touched by the personal mode of presentation, but angered by the curator and his manipulative, unassuming style.

Restorative nostalgia, believing its project is reinstating the 'truth' of the past, is the kind of remembrance given to "total reconstruction of monuments of the past," to a return of national symbols and myths, to conspiracies. Etymologically it has its roots in re-staure -- re-establishment. It suggests stasis and a return to the prelapsarian state. The invented traditions circulating the restorative drive suggest a sensed loss of community, offering, in Hobsbawm's phrase, a “comforting collective script for individual longing." The invented tradition, of course, is not created out of nothing and it can be emancipatory, not just conservative. Its appearance may afford multiple imagined communities and forms of belonging, not just national and ethnic ones. (We're back with Eagleton now and the sense of tradition that can be central for radical politics.) The 1956 Museum seems so uncomfortable for James because it marries an individual, personal -- almost lonely -- campaign with a nationalist, conservative one. Where the grand gesture for reconstituting national unity is undertaken by the same man who changes the vase water every day. The sense of purpose and vitalism endlessly circling and deeply invested in what is, literally, a past battle.

For the restorative nostalgic, home, or the nation here, is "forever under siege, requiring defence against the plotting enemy"; it is not a place "made of individual memories but of collective projections and 'rational delusions'." The nuance and ambivalence of history is forgone for a paranoid view of the world, a "fantasy of persecution". Tradition is the fortification to hold these impostors at bay, to bind 'we' against 'them': "'they' conspire against 'our' homecoming, hence 'we' have to conspire against 'them' in order to restore 'our' imagined community". Conspiracy theories have a tendency to flourish after revolutions. There has been a rise of conspiracy theories around this second millennial turn. These two tendencies coalesce in one particular formation given to embracing this nationalist nostalgia:

It is not surprising that many former Soviet Communist ideologues have embraced a nationalist worldview, becoming 'red-and-browns,' or Communist-nationalist. Their version of Marxism-Leninism-Stalinism was revealed to have the same totalizing authoritarian structure as the new nationalism.

Nostalgia, Boym remarks, is a "double-edged sword." It is "an emotional antidote to politics, and thus...the best political tool." She explores this largely in a Russian setting. Her operative framework comes when she poses questions as relevant to her project as mine:

Nostalgia, Boym remarks, is a "double-edged sword." It is "an emotional antidote to politics, and thus...the best political tool." She explores this largely in a Russian setting. Her operative framework comes when she poses questions as relevant to her project as mine:While aversion to politics is a global phenomenon, in Russia mass nostalgia of the late 1990s shared with the late Soviet era a particular distrust of any political institutions, escape from public life and reliance on indirect language of close interpersonal communication. What made everyday Soviet myths, affections and practices survive long after the end of Marxist-Leninist ideology? How is nostalgia linked to the beginning and the end of the Soviet Union?

No comments:

Post a Comment